Was there life before the corona pandemic? Yes, but how do I write about traveling in such different African countries like South Africa, Rwanda, Uganda and Kenya just a few weeks before the world came to a standstill due to Covid-19? This blog is about more than one story. It is about the beauty of Africa, about its people, its complexities and its history we have seen on this journey. This article will pull you back and forth between those four countries as I explore the differences as well as commonalities between them. It has snippets of our own personal memories from living in South Africa many years ago, therefore it will also pull you back and forth in time. When this makes you curious, please do keep reading.

Francien and I started our 4500 km road trip in Cape Town, prime global tourist destination for its beautiful Table Mountain backdrop, coastal sceneries and nearby wineries. We headed north to the quaint coastal resort of Paternoster and continued to Hermanus on the South coast. After spending time together with friends, we drove east on the Garden Route. We crossed rivers, drove on winding passes, enjoyed spectacular coastlines, the verdant mountains and after a scenic five-hour drive reached Knysna. Here again we spent time with friends and used the opportunity to explore the estuary of Knysna Bay dominated by steep 100-metre cliffs jutting into the ocean. After a few days, Francien and I drove 1200 km to Johannesburg, crossing the Karoo with its koppies, the sheep, the metal windmills, isolated farms, the watering tanks, endless grasslands, contrasting rocky outcrops and endless straight road. When we reached the busy rush hour traffic of this three-million-metropolis we passed the shanty towns of Soweto.

After a few days staying with friends in the wealthy northern suburbs, Francien and I flew to Kigali, the capital of Rwanda. Our first impression driving from the airport to the city center: poor, but clean and well organized. The next morning all shops and businesses were closed because the people did communal service (cleaning the streets and parks, painting walls, building houses for the poor). Rwanda is the new Africa: no plastic bags allowed, pothole-free roads and we saw fiberglass optic cable being laid along the roads in the rural areas. On a hill in Kigali in a neighborhood of embassies and mansions we had a delicious sunset dinner like in any other sophisticated restaurant in the world.

After two days we drove seven hours to the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest across the Ugandan border. We drove through green and terraced hills with towering stands of silvery eucalyptus trees. Men and women gathered on colorful markets along the road, selling their produce, sheep, goats and cows. Crossing into Uganda felt like passing from this new Africa into an old one. There was a stark contrast between Rwanda and Uganda. The Gatuna border post was an introduction to the poverty in Uganda. Inside the dilapidated immigration office, the Ugandan officer took my arrival card, threw it on a pile of other cards on a table next to her. The table was full, so most cards ended up on the floor. She stamped my passport without further looking and waved us through.

We drove on winding roads through rolling verdant hills and valleys. Alongside the road we saw wood-fired furnaces used to bake bricks from the local red clay. There were small-hold-farms sustaining families with many children amid tea plantations, banana's, sugar cane, sorghum, coffee, millet, cassava and peanuts. It seemed to be a fertile land. We saw few cars driving around, instead the people used their bikes to carry bags with charcoal, milk containers, bundles of grass and even furniture.

The last two hours we bumped along a terrible road. Goats scurried across. Kids wearing no shoes, ran to the side of the road, watching us and waving enthusiastically. Some shouted ‘Amazung' (‘white’ man).

Bwindi Impenetrable Forest is a collection of rugged mountains and valleys near the borders of Rwanda and Congo. This forest is home of the endangered mountain gorillas, but also of the pygmies indigenous people.

We stayed in the tiny village of Buhoma close to the parks gate. There were no cars, no TV's, no concrete building, no streetlights, only bad untarred roads. Houses were made of self-made bricks, some out of wood and drinking water was provided at communal water taps. We visited the local orphanage where the children performed singing and dance to get a donation. The other interesting activity for tourists like us to see was the Women Empowerment NGO center. The sense of poverty was palpable.

An armed Park Ranger gave us an escort. He said: ‘Scarcity creates temptation to steal and scaring of rich tourists would cost dearly.’ The nearby entrance of the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest National Park was the reason why we were there. And of course, we visited this world-famous park of which more hereafter.

A few days later back in Kigali, before we could enter the international airport, our fully loaded car was taken through a state-of-the-art vehicle scanner to check for explosives and other illicit materials. Impressive High-Tech in the middle of Africa!

Our 90-minute flight to Nairobi was uneventful. This city looks like the stereotypical African city you and I have seen on TV: people filling the streets, vendors, cars, trucks, motorcycles crisscrossing, policemen trying to direct the chaotic traffic. But somehow everything seemed to be working. The few shopping malls looked simple, carrying international brands, but with no glitter. There were a few power dips when we ventured out for some shopping.

The next day we were rewarded for the long travel with a stunning view across the Rift Valley. The clouds shaded the valley stretching into the Masai Mara and Serengeti.

Lake Nakuru was also on our itinerary. Here the poverty was like we saw in Uganda. Children waved at us asking for sweets. One boy wanted to throw a piece of wood against our car, if not for our guide to shout no doubt some very threatening words.

We also drove to Lake Naivasha on the Mombasa - Kampala road. Busy with trucks, this tarmac single carriage way crosses many settlements. These were busy places servicing the trucks, selling food to the drivers in middle of road, offering shack-hotels, markets, repair shops. Lake Naivasha was used by the British as stop for their postal planes on route to South Africa. It now is a National Park known for its unique water wildlife.

Looking at this itinerary, it is screamingly obvious that we have come across an incredible variety of nature, cultures and people. So how can we make sense out of all those different impressions we had during this journey? First comes to mind is that people from around the world travel to this continent foremost to see its magnificent wildlife. For good reasons! Around the Cape wide and clean white beaches with washed up kelp are for endless walking. Guano on top of rocky outcrops, small bays, rock-pools and seabirds. These pristine and nutrient-rich waters of the Benguela current teem with fish, sea birds like cormorants and plovers catching them. The famous South-Easterly wind picked up during the course of the day and cleared the morning sea fog. Francien and I walked the secluded beaches and dunes while the cold and dark blue ocean looked frightening. We watched the cray-fishers bringing in their cages onto the beach in small one-engine-boats and were happy to see that these beaches were still clean. And yes, the famous Garden Route and iconic Karoo are indeed scenic and unique, but much has been written about these, so allow me to skip to less known wildlife treasures in this vast continent.Dare I say it, we have done many exciting safaris in South Africa and Namibia, but Africa keeps surprising us. Take the Mountain Gorillas in Uganda: we headed up one of the volcanic mountains in the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, searching for these endangered primates.

Together with our guide and an armed ranger we scrambled upward waist high through the wet thicket. Thorny brambles brushed my cloth and ripped into my trousers and shirt. We were at 1900 meters elevation, having started a few hours earlier at 1500 meters. Then we smelled the gorillas. The bush was so thick, I could not see one sitting only seven meters in front of me, but finally I did. The sight of that first gorilla literary stopped me in my tracks. That moment quickly passed. ‘Get closer, get closer.’ our tracker gestured. In awe we watched a male gorilla. I paused to take in the scene of this huge silver back. Honestly, these animals are bigger than you expect. This group of eight gorillas our trackers managed to find kept slowly moving, feeding on leaves and berries. For us it was hard to follow them, the humid air stuck my clothes to my skin. If you have not seen this with your own eyes, you probably have seen it on TV. But being physically only a few meters from these animals; it is something unique. It reminded me of our experience with the gentle Orangutan in the forests of Sumatra, but those apes felt much more like humans. They did look us in the eyes with a real human expression, unlike these mountain gorillas. Their size and appearance felt all but friendly to me.

And then there was this cold morning in the Masai Mara National Park where we climbed into the basket of a hot air balloon. A few minutes later we enjoyed spectacular views with clearing skies, crossing vast savanna dotted with lonely acacia trees, meandering rivers, small hills, flooded dirt roads with no cars. Elephant herds, buffalo herds, hyena, hippo, giraffe. A smooth one-hour flight between 3 and 100 meters over the terrain. After that, we drank champagne and ate a full breakfast at decorated tables on a small hilltop shaded by a single acadia tree, amid the endless stretching savanna. We made pictures of the vultures waiting in a tree close by, hoping we leave some scraps. Woow, it all had this colonial feeling. I wondered: what if we would not come here? Would it be better for the locals, even for the wildlife? It is like a two-edged sword, bringing in hard currency as well threatening the pristine nature and unique way of life of the locals.

Back in our 4x4 Landcruiser, bumping on the flooded dirt tracks we saw four cheetahs, lions with cups, elephants, Topi's and lots of other antelopes, warthogs, giraffe, buffalo, zebra and vultures circling in the sky. I can not begin to list them all here.

Seasonal rains made many roads impassable. We bounced along furrowed dirt tracks, through mud slicks, crossing streams. Just before sunset our guide Obi received a call for help on his smartphone. His colleague got stuck in the mud. After 30 minutes we arrived at the scene and after a few attempts managed to pull him out of the mud.

‘In the bush people help each other without asking questions.’ Obi explained to us. ‘Jambo.’

And in the Amboseli National Park on one clear early morning we enjoyed a picture-perfect view of Mt. Kilimanjaro with herds of elephants, buffalo’s, a few hippo’s and hyena's roaming the grassland. Yellow bark acacia trees dominated the hilly landscape. The blue African sky was indeed bigger!

When we stayed at Lake Naivasha, one morning we woke up by screaming fish eagles. We drove to the Mt. Longonot volcano and hiked up to its rim. When we started our hike, the rim was partly covered by rain-clouds, but the rising sun cleared the African skies. After three hours we reached the summit at 1900 mtr. It made for magnificent hiking with views across the Great Rift Valley. On top we smelled the sulphur in the clouds coming from the steam vents in the nearby Hell Gate park area. This is still raw nature, with more views into the crater, the nearby Naivasha lake and the verdant Rift Valley.

This diverse nature and wildlife has shaped the continent and its people through-out its history. Much of the European African history started on the southern tip. In the 17th century, the Dutch built a small settlement in what is now Cape Town. Here Francien and I walked into the Groote Kerk. This Dutch Reformed church was founded by Van Riebeeck and its Gothic style building dates from the 18th century. Wealthy families and boarding schools in those days had their own dedicated enclosed pews. In one corner there were wooden enclosed pews with chain locks. Witnesses to those slavery days, that is where the slaves sat there during mass. The Dutch 'orgel' is the biggest of its kind in Africa and the wooden pulpit was beautifully hand-crafted. I read the wooden memorial plaques from prominent Afrikaner families on the paneled walls, giving a hint of life during those old days.

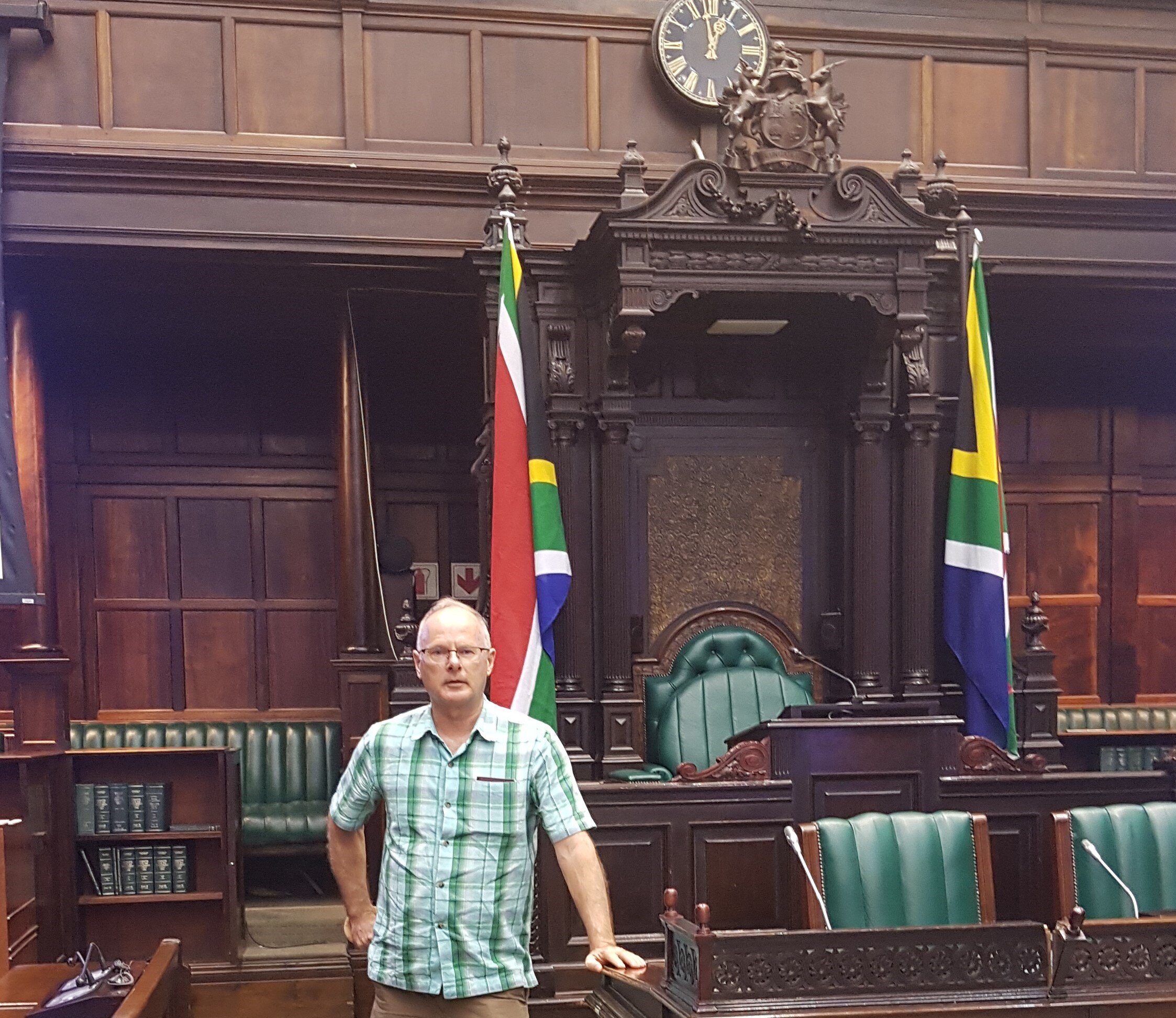

We visited the old parliament where Hendrik Verwoerd was murdered and apartheid was ruled. The buildings are from the British period, built with bricks with Royal seals. The many civil servants going about their daily work here looked relaxed and there was an informal atmosphere.

It is 2020, but a little bit we were taken back to 1982 when Francien and I lived in Johannesburg. A visit to the Carlton Centre in downtown was a weekend treat. And here we were again, standing on the Top of the Carlton with a sense of nostalgia. The view from the 50th floor felt familiar. Isn’t it strange that after all those years we still remembered the yellow goldmine dumps (no more), the checkered streets in downtown, the expensive mall and hotel below which back then exceeded our budget? I still recall the building as almost touching the sky, but now what does 50 floors mean considering the skylines around the world? Sadly, now the centre was run down, and the hotel out of business. Francien, our friend Anneli and I were the only visitors around, - tourists shun this place. It is a notoriously crime ridden area, but fortunately we did not feel threatened. However, we made sure we had left before darkness!

The three of us also visited the Constitution hill close to downtown. It is here were the constitutional court of South Africa has been built. It all has a very African feel: airy, simple and a relaxed atmosphere. This former fort was built by Paul Kruger and during the apartheid era used as prison. Directly adjacent to this, the notorious prison 4 in which Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi were held before their trails.

The exclusive Rand Club was founded in 1887 when gold was discovered in the Witwatersrand. It is still housed in a six-story neo-baroque building in the city centre. When we entered the club, I was impressed by the large double staircase and wood paneled walls. We enjoyed having a drink at its 31-meter-long bar. It is the longest bar in Africa. In the bar there was an old original shoe polish chair. Commemorative plaques of regiments and famous people like Oppenheimer, Paul Kruger and Cecile Rhodes decorated the dark walls. Upstairs the ball room and armory exude more of the old British colonial days.

Walking distance from this once men-only establishment are the former Anglo-American Head Quarters. This massive building with its impressive stone entrance steps overlooking the Leaping Springbok monument exemplifies the power of gold discoveries. Life size gold mining artifacts like oar-crushers and compressors are nicely displayed in the pedestrian area of New Town. Johannesburg was built on gold.

Back to Eastern Africa again, the historic Stanley hotel in the middle of Nairobi also has this colonial atmosphere: dark wood furniture and paneling, thick carpets, in the exchange bar manual fans mounted to the ceiling. It has high ceilings, a veranda with old fans and bell boys in tunics attending to the guests. Stepping through the doors of this hotel is not only like walking from the poor world into the rich, but also from the modern into the colonial past. I hang a message on the thorn tree in the restaurant like people have done since more than 100 years. We enjoyed drinking a cold frothy Tusker beer. This all did not only remind us of the Rand Club in Johannesburg, but also of the Raffles bar in Singapore and the Selangor Club in Kuala Lumpur. The British knew how to leave their marks!

In Rwanda it struck us that we could not see any dogs or cats. ‘Why not?’ we asked our driver. He shook his head and said. ‘Because these animals ate the corpses of people during the genocide. People do not want to be reminded of those terrible scenes.’ I was expecting a grand monument to commemorate the victims of the genocide he referred to. But instead we walked between simple concrete museum and documentation center buildings and memorials marking a mass grave in which 250000 Tutsies have been buried in 1994. The gardens around the genocide memorial overlooked the heart of Kigali. What stuck to me was its simplicity and yet a place to reflect.

The history in this part of the world is very much linked to the colonial past and the direct results of that. These are in many cases the causes of the present-day problems we have seen with our own eyes.

When we stayed with our friends in the seaside town of Hermanus in South Africa, a police helicopter flew over the house. ‘What are they looking for?’ I asked.

‘Looking for abalone poachers, which is a big problem here.’ the sobering answer was. Whether on small or big animals, poaching was still happening in all the four countries we have visited. In Nakuru National Park in Kenya, known for its big Rhino population, the guards at the park entrance carried machine guns and when we drove through the park we saw an anti-poaching squad on foot-patrol. Like what we saw in Bwindi Impenetrable Forest National Park in Uganda, where many rangers carrying rifles protected the gorillas against still active poachers. Much good work is being done.

Down at the Cape we experienced our first load shedding. We dined with battery lights (the restaurant cooked on gas bottles), because the area was without power for many hours. One time when we approached a traffic light on a busy intersection, suddenly there was another power-cut and all lights stopped working. But people driving their cars and motorbikes instantly reacted in a responsible way, giving way to others and avoiding any problems: they were used to this!

We drove past an illegal settlement which was recently built on top of a freshly covered landfill. Toxic methane gasses still came out of the soil, putting families who lived in the tin roofed sheds at risk. But the people wanted to move here. These migrants moved from the impoverished Eastern Cape province to the Western Cape, desperately hoping to find jobs and a better life. Déjà vu, that is what migrants do all over the world.

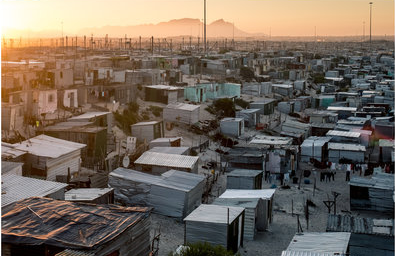

In Cape Town we saw many homeless people on the streets, even children, from all colours. Driving through the Cape Flats, I watched the endless shantytowns with the Table Mountain on the horizon. Townships like these on the outskirts of cities, villages and towns we crossed looked very much like we remembered them from back the 80’s. Corrugated sheds, electric wires hanging low, untarred roads, rubbish scattered around, advertising billboards/plastered along roads, people walking, children playing and few cars. I never get used to these depressing sights.

And then there was this different world, the world of the privileged. On the boulevard in Cape Town we saw foremost young ‘white’ (with this term I do NOT want to stigmatize nor discriminate in any way) men and women, jogging, walking their dogs, skating, biking or simply sitting on a bench enjoying the rough Atlantic Ocean. In Knysna we stayed with friends on an estate which was a wealthy bubble. There were no security guards required because it was located in a remote area away from the towns and settlements. When I did my morning run, I heard pigeons, saw guineafowls, Ibis and weaverbirds darting around their nests. The sky was blue, and I enjoyed the pleasant scent of the crispy air. It reminded me of our stay in Dainfern estate many years ago in the northern suburbs of Johannesburg. And even further back in time, this scent of the trees and shrubs recalled memories of our lives in Birch Acres in the 80’s. Back in those days of apartheid, it was a designated ‘whites only’ suburb in Johannesburg. But fast forward to today, it felt as in those old days when ‘black’ people did the gardening, were the handymen and walked the dogs. ‘White’ workers drove the pick-up trucks loaded with ‘none-white’ workers in the back. This time again I saw mainly ‘white’ people driving in expensive cars and playing on the golf course. Do not get me wrong, but observing this was confusion considering the ‘white’ people make up only 10% of the total population : did I miss anything?

And what about the scene in the middle of Johannesburg when we watched young foremost ‘white’ high school graduates arriving in their Lamborghini cars at the exclusive Rand Club to attend their graduation party? This all happened while homeless people stood just meters away on the other side of the road watching the security guards directing the traffic. Again, I tried to understand what those extreme contrasts meant. Can I get my head around this?

Everywhere we went in South Africa there was this sense of potential crime and violence: we saw private security patrol cars, electrified garden fences, burglar bars, security gates, fortified gated communities, heavily armed policemen and security guards in front of most business and buildings. The huge inequalities we have seen are certainly one cause of this.

A world away in the Kenyan savanna we stayed in the luxurious lodge with a modern solar power plant and all the five-star comforts you can imaging only a few hundred meters away from a Maasai village where the people had no electricity, running water nor sewages, simply living of their cattle and tourism,.

In Nairobi former street kids showed us around the poverty-stricken downtown area: woow, what an experience that was. That area is a maze of cramped, makeshift shops and crumbling brick and tin roof houses. The roads were dirty, some small rubbish piles still burning. Tightly packed, decrepit housing inhabited primarily by poor people. We walked on unstable pavements, dirt tracks, crossing potholed roads with chaotic traffic of matatu's, cars, bikes and tuk-tuks. Poverty pure! The Mathare River looked and smelled like an open sewage and the stench of garbage in some streets was intense. The street kids told us about the violence, crime and flying toilets (bags with faeces they threatened to throw to anyone unless they would hand over some valuables). We talked to a boy (in his early twenties) and he showed us how he sniffed a mixture of glue-petrol-weed from a plastic bottle: was he trying to forget about the hopeless situation he was born into? In dusty and busy streets, we continued walking past men and women hawking fruit and vegetables, a boy pedalling a rickshaw, beggars and scrap collectors. Traders sold old clothing, used shoes, cement, food, second-hand car parts and drums with clean drinking water. 'Mzungu!' (‘white’ person) some guys called us in a provocative way. ‘The Indian and Muslim communities live and work in their separate parts of this crime ridden part of town.’ one of the kids pointed out to us. ‘Many live here hand-to-mouth.’ he continued.

The Royal Nairobi Golf Club was just a few hundred meters away from this area and we could see the glittering business towers of the CBD on the horizon. Our luxurious hotel was a mere ten minutes Uber ride away. Yet another overwhelming example how big the rift between rich and poor is! I felt sad that people live such fragile lives in an era of global abundance. I want you to see what I saw and smell what I smelled, but that is impossible

In Kenya I was in the fortunate position to visit a Maasai village on my own. 125 People of four families formed a traditional polygamic group. They still lived a semi-nomadic and subsistent life. These lanky people wear distinct colorful beads, red robes and distended earlobes. Built around a kraal, the huts were made of tree branches, dung and hides. Inside the hut I visited it was dark, with no lightning and no windows. There was only a few sleeping spots and a tiny fireplace inside. Thorn bushes around kraal and vicious looking dogs protected their cattle against the hyenas. ‘We drink the blood of our cows mixed with milk.’, the young man explained to me in perfect English. ‘In this village the men have four wives.’ he continued. His friends showed me how they boil plants for medicine and performed a dance for me. The Adamu, the traditional jumping-dance, is a competition between the men; the higher a man jumps, the more attractive he is for the women. Carrying their spears and chanting with a deep guttering vibe, they indeed jumped at least 40 centimetres without much effort. There was no electricity and only one water well provided for them all. ‘We have a latrine outside the camp and clean our bottoms with stones!’ he explained to me with a big smile on his face. Their way of talking was direct, even bluntly. At the end they were pushy about getting some donations from me. What will they do with my donation? When I left, I felt conflicted about this visit. A uniquely different and simple live which will no doubt be assimilated into the other 42 Kenyan tribes. Their culture is already changing rapidly: my Maasai guide did finish high school in Nairobi, standing with one leg in this traditional past and the other leg in the modern times; the beads the women used for the crafts they sell to the tourists are produced in China and the younger men in the village had no problems using my smartphone to make pictures.

The Kikuyu is the dominant tribe in Kenya, but they mingle with all other tribes without any problems. When we walked with those former street kids in downtown Nairobi, one of them said: ‘Only during the national elections the tribal differences are polarized for political gains, often resulting in violent clashes we have in the past on TV.’ That reminded me of the colonial way of ruling people: divide and conquer. It seems not much has changed.

In the dense mountain forests of Uganda we visited a pygmies cultural center in Buhoma. Our local guide explained that these Baka people traditionally lived deep in the forests as semi-nomadic hunters. These small people (average height for men is 1.55 metre.) have been driven out of the park to protect the Mountain Gorillas and now are forced to assimilate with the local tribal communities. Spread around this tiny village, several Pigmy families lived on designated plots in their traditional thatched huts. Most of them had no work and received some little income from the few tourist visiting their villages. It was a bewildering experience; not sure this was the right thing to do. How must it feel for them to show their traditional way of life to ‘rich’ tourists? But I guess our donations made a small contribution to these destitute families.

All these challenges have a profound effect on the people we have met. In particular in South Africa, the mood of all foremost ‘white’ friends and old colleagues (sorry, but that is the bubble we lived in) was gloomy to say the least. ‘The government services are constantly deteriorating. We have power cuts, the roads need maintenance, our education system is not working and the medical facilities are inadequate.’ we kept hearing from the people we talked to. They were anxious about the future and in particular the future of their children and grandchildren. Nobody seemed to have a solution to stop the country from further declining. Leaving the country for young South Africans was preferred by many. They were unhappy about politics, the corruption, the reversed discrimination and incompetence of some of the leaders. Nevertheless, it was great again to meet up with so many long-time friends. They still have that can-do mindset and are committed to help built a better future for their country. And we saw again for ourselves how magnificent this country is.

During this trip, we saw most people having internet access via their (sometimes cheap) smartphones. Tack savvy was also Obi, our enthusiastic and knowledgeable guide through-out our stay in Kenya. He had left his village and started a new life in Nairobi. We met his farther who still lived in the house Obi was born, far away from any cities. He came to our car, welcomed us and gave me a token present as was their custom. Before he said goodbye, he hand-kissed me, which I felt somewhat embarrassing.

Coming from South-East-Asia ourselves, what struck me is that the people we met and observed in Africa seem to be more energetic. They are expressive, tell jokes, enjoy singing and smile a lot. We saw many young entrepreneurs running coffeeshops and restaurants in creative and inspirational ways. We always felt welcomed.

Francien with long-time friend Anneli in Johannesburg

This trip was both a great adventure and a lesson about African complexity and diversity. It was time to fly back to Kuala Lumpur. When anywhere in the world you fly 30000 ft over land, there is always somewhere a light to see. But looking from my airplane window, I saw none. Scanning the dark night for any light I realized how big this continent is, the reason why so many travellers come here to do a safari unlike any other place in the world.

But with that we have seen signs of ‘over-tourism’ which has become a global problem. In the Maasai Mara game park we saw 15 safari jeeps, filed with camera clicking tourists, blocking the path of a couple of hunting cheetahs. In the Nakuru game park I saw plastic waste washed in from the river in a lake where lesser flamingo’s were foraging. When I visited the Maasai village, I saw an American tourist accompanied by his bodyguard, carrying in a provocative way a machine gun while strolling through the kraal: this epitomizes a total disrespect for other cultures! Africa needs tourists and the hotel managers, park rangers, or guides and drivers were all very aware of that.

The Africa we have experienced on this trip is the cashless-terrace-cafe in Nairobi, the solar panels in the middle of the savanna and the Maasai drinking blood while tourists fly in a hot air balloon above. It is about slums with destitute people and luxurious game lodges for a hand full of tourists, shacks in slums adjacent to seven-bedroom mansions in gated communities, a pigmy hunter in front of his hut a few hundred meters from our lux chalet. We must have seen some of the biggest wealth gaps anywhere in the world.

Allow me to say that Francien and I are experienced world travellers. But nowhere we have been we experienced so many contrasts. We strolled through the rich Waterfront area in Cape Town and met the street-kids in the slums of Nairobi. We visited the Koeberg nuclear power station where 2x 950 MW reactors produce clean electricity while that same evening we witnessed a power cut because the distribution system is short of collapsing. The state-of-the-art vehicle scanner at the Kigali airport was a far cry from the dilapidated Ugandan immigration ‘shed’ when we crossed from Rwanda. The clay furnaces along the road in Uganda did not resemble the modern high rises in downtown Kigali. Smartphones and high-speed internet must be out of his world for that old pygmy man we met.

We drove next to the newly constructed railroad line Mombasa - Kampala, built by the Chinese. We saw many signboards with names of Chinese construction companies not only in Kenya but also in Rwanda and we were told there are indeed many Chinese building factories, roads, railways, office towers and powerplants. These construction sites are signs of further progress.

What is the takeaway here? The Africa we experienced is complicated, full of contradictions, no doubt beautiful and making progress. Thank you for reading this article.